There’s not much more to say about this one: it was a fabulous trip. It was very special: the scenery, the company, the amazing country and people, the walking, the guides and the length of time away from reality. (Almost three weeks! Unheard of!)

The article ran in the March-April 2018 issue of Outdoor, and the photos were all mine as well.

Over the hill in nepal

Megan HOlbeck celebrates a twin Milestone on a two-week trek to the Gokyo lakes

My twin sister and I trudged up the hill in a chorus of puffing. We’d stopped talking for the first time in 12 days, the catch up not as important as being able to breathe. The long, brown slope of Gokyo Ri might have looked like a nondescript Snowy Mountain ridge, but it sure didn’t feel like it.

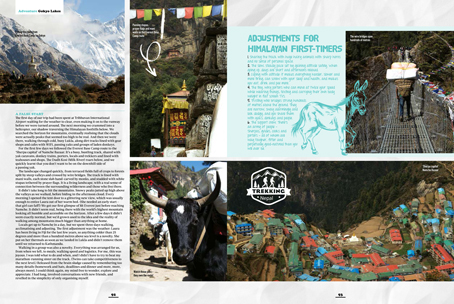

Up ahead the fluttering of prayer flags announced the summit (5360 metres). After another ten minutes of plodding, we reached the top with its panoramic view of the Himalayas. Jagged snowy mountains lined the horizon, including four of the world’s six 8000 metre peaks: Mt Everest, Cho Oyo, Makalu and Lhotse. Below lay a jumbled grey river of glacier and moraine and the browns of smaller peaks, the two dazzlingly blue lakes in the valley below breaking up the barren, high-altitude colour scheme.

I hugged Laura, first making sure I wouldn’t knock us both over the edge. (Mum and Dad would not have been happy!) We’d reached the high point of the trip, figuratively speaking at least, and it had been more beautiful and rewarding than we’d imagined, as well as both harder and easier. It was also giving us a new insight into ageing: we’d come here to celebrate our 40th, but we didn’t just feel middle aged, we felt half dead.

A world away

It was all Laura’s fault. ‘Why don’t we celebrate our 40thby going trekking in Nepal?’ she’d asked two years earlier.

At the time I’d been feeding a newborn, doing jigsaws with my two other kids, while also setting up a website and cooking dinner. I scoffed, outlined the thousands of reasons why it was completely impossible, and forgot all about it. Until a year later, when I found myself researching trips, trekking companies and flights. A week later, we’d both paid deposits on World Expedition’s trip to Gokyo and the Renjo La, a 13-day trek in the Khumbu region of Nepal.

A false start

The first day of our trek had been spent at Kathmandu Airport waiting for the weather to clear, even making it on to the runway before we were turned around. The next morning we crammed into a helicopter, our shadow traversing the Himalayan foothills below. We searched the horizon for mountains, eventually realising that the clouds were actually peaks that seemed too high to be real. And then we were there, walking through cold, busy Lukla, along dirt tracks lined with gear shops and cafes with wifi, passing yaks and groups of laden donkeys.

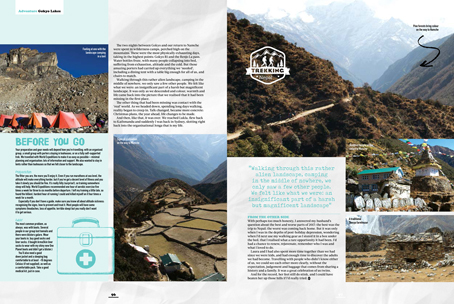

For the first few days we followed the Everest Base Camp route to the ‘Sherpa capital’ of Namche Bazaar. It’s a busy, bustling track, shared with yak caravans, donkey trains, porters, locals and trekkers and lined with teahouses and shops. The Dudh Kosi (Milk River) roars below, and we quickly learnt that you don’t want to be on the downhill side of a passing yak.

The landscape changed quickly, from terraced fields full of crops to forests split by steep valleys and crossed by wire bridges. The track is lined with mani walls, each stone slab hand-carved by monks, and studded with white stupas tethered by prayer flags. It is a living landscape, with a real sense of connection between the surrounding wilderness and those who live there.

It didn’t take long to hit the mountains. Snowy peaks jutted up high above the valleys as we walked, before hiding in the afternoon cloud. Every morning I opened the tent door to a glittering new view, which was usually enough to entice Laura out of her warm bed. (She needed an early start – that girl can faff!) We got our first glimpse of Mt Everest just before reaching Namche. It didn’t seem real, being there with the world’s highest mountain looking all humble and accessible on the horizon. After a few days it didn’t seem exactly normal, but we’d grown used to the idea and the reality of walking among mountains much bigger than anything at home.

Locals get up to Namche in a day, but we spent three days walking, acclimatising and adjusting. The first adjustment was the weather: Laura has been living in Fiji for the last few years, so anything colder than 25 degrees and more than a hundred metres above sea level is a novelty. She put on her thermals as soon as we landed in Lukla and didn’t remove them until we returned to Kathmandu.

Walking in a group was also a novelty. Everything was arranged for us, from when we left, to meals, walking speed and logistics. For me, this was joyous. I was told what to do and when, and I didn’t have to try to beat my marathon-running sister on the track. (Twins can take competitiveness to the next level.) Released from the brain sludge caused by remembering too many details (homework and hats, deadlines and dinner and more, more, always more), I could think again, my mind free to wonder, explore and appreciate. I had long, involved conversations with new friends, and revelled in the simplicity of only organising myself.

The landscape changed dramatically around Namche. This horseshoe-shaped town is perched above a deep valley and ringed by peaks, and from here on up, it is all about the mountains. We left Namche on the fifth day, becoming an insignificant part of a grand setting. From a stupa jutting out on an exposed ridge the view opened up, showcasing Ama Dablam, Mt Everest, Nuptse and Lhotse and hundreds of other small peaks. (You know, only 6000 metres or so high!) An hour later we turned off the Everest Base Camp trail and the whole flavour of the trip changed. There was now the occasional person rather than a steady stream of folk, and the villages were much more spaced out. Instead there were forests of rhododendrons and silver birch, waterfalls that pitched down hillsides and patches of snow hidden in dark corners of the trail.

The effects of altitude also became more noticeable. Group members suffered from headaches, stomach complaints and sleeplessness, and every movement took more effort than it should. After putting away a sleeping bag I needed to catch my breath, and running more than ten metres was out of the question. Most nights it snowed, and Laura was now walking in a minimum of four layers.

The stupas and mani walls disappeared, as did the crops, replaced by seasonal yak pastures divided by stone walls. By the time we reached the Gokyo Lakes on the tenth day of walking, the landscape was stunning but barren, with a high-altitude palette of muted greys, browns, whites and greens.

At 4700 metres, this is the world’s highest freshwater lake system. It’s also got to be among the most beautiful: the water is a brilliant blue, fringed with ice, studded with ducks and surrounded by a standing army of rock cairns. Oh, and there’s a few mountains scattered around (only the world’s highest and most famous), as well as a glacier or two. All in all, it’s a pretty awe-inspiring place, and the next few days were the best of the trip.

Our first and only night in a teahouse was at Gokyo, perched by the side of the lake. Up until then I’d shared a tent with Laura and her increasingly stinky feet in one of World Expedition’s permanent campsites. These were a world away from the usual: each was complete with a dining hall, stand-up tents with camp beds and mattresses, toilets and running water. We were spoilt: woken up with tea in bed and a warm bowl of ‘washy washy’, and fed three courses at every meal. It was generally delicious if rather carb heavy – roti, rice, pasta and potato in the same meal was not unusual – and I always had seconds, and sometimes thirds. (And still lost weight – you’ve got to love altitude sometimes…)

The two nights between Gokyo and our return to Namche were spent in wilderness camps, perched high on the mountains. These were the most physically exhausting days, taking in the highest points: Gokyo Ri and the Renjo La pass. Water bottles froze, with many people collapsing into bed, suffering from exhaustion, altitude and the cold. But those amazing porters had carried up everything we ‘needed’, including a dining tent with a table big enough for all of us, and chairs to match.

Walking through this rather alien landscape, camping in the middle of nowhere, we only saw a few other people. We felt like what we were: an insignificant part of a harsh but magnificent landscape. It was only as we descended and colour, warmth and life came back into the picture that we realised that it had been missing in the first place.

The other thing that had been missing was contact with the ‘real’ world. As we headed down, spending long days walking, reality began to creep in. Talk changed, became more concrete: Christmas plans, the year ahead, life changes to be made.

And then, like that, it was over. We reached Lukla, flew back to Kathmandu and suddenly I was back in Sydney, slotting right back into the organisational Jenga that is my life.

From the other side

With perhaps too much honesty, I answered my husband’s question about the best and worse parts of 2017: the best was the trip to Nepal; the worst was coming back home. But it was only when I was in the depths of post-holiday depression, wondering when I’d next use my walking gear as I stored it in a box under the bed, that I realised what a rare opportunity it had been. I’d had a chance to renew, rejuvenate, remember who I was and what I loved to do.

Laura and I had also spent more time together than we had since we were kids, and had enough time to discover the adults we had become. Travelling with people who didn’t know either of us, we could see each other more clearly, without the expectation, judgement and baggage that comes from sharing a history and a family. It was a great celebration of us twins.

And for the record, her feet still do stink, and I could have beaten her up those hills if I’d really tried.

Adjustments for Himalayan first-timers

Sharing the track with huge hairy animals with sharp horns and no sense of personal space.

The slow, steady pace set by gaining altitude safely. When going up, days are short and afternoons relaxed.

Coping with altitude: it makes everything harder, slower and more tiring, can screw with your sleep and health, and makes you eat, drink and pee more.

The tiny, wiry porters who can move at twice your speed while wearing thongs, texting and carrying their own body weight in flat screen TVs.

Trusting wire bridges strung hundreds of metres above the ground. They are narrow, sway alarmingly and look dodgy, and you share them with yaks, donkeys and people.

The support crew. There’s an army of people – Sherpas, guides, cooks and porters – all of whom are way tougher, fitter and perpetually good-natured than you will ever be.

Before you go

Your preparation and gear needs will depend how you’re travelling: with an organised group, a small group with porters staying in teahouses, or on a fully self-supported trek. We travelled with World Expeditions to make it as easy as possible – minimal planning and organisation; lots of information and support. We also wanted to stay in tents rather than teahouses so that we felt closer to the landscape.

Preparation

The fitter you are, the more you’ll enjoy it. Even if you run marathons at sea level, the altitude will make everything harder, but if you’ve got a decent level of fitness and you take it slowly you should be fine. It’s really hilly (surprise!), so training somewhere steep will help. World Expeditions recommended one hour of aerobic exercise five times a week for three to six months before departure. I left my training a little late, so found the hilliest, hardest hour of running I could and killed myself on it four times a week for a month.

Especially if you don’t have a guide, make sure you know all about altitude sickness: recognising the signs, how to prevent and treat it. Most people will have some symptoms (headaches, loss of appetite, terrible sleep) but you really don’t want it to get serious.

Gear

The most common problem, as always, was with boots. Several people in our group lost toenails and there were blisters galore. Wear your boots in, buy good socks and liner socks. (I bought ArmaSkin liner socks to wear with my shiny new One Planet boots and didn’t get a blister.)

You’ll also need a good down jacket and a sleeping bag comfortable to at least

-10 degrees Celsius (if not supplied), as well as a comfortable pack. Take a good medical kit, just in case.