I’m very proud of this piece, which was published in the July/August 2018 issue of Outdoor magazine. I got to interview some amazing women about a topic that’s very close to my heart.

Keeping the Home fires burning

Megan HOlbeck explores how parenthood and gender roles affect adventure

Whenever I read anything by men on trips, I think of the women holding the fort at home. Men seem to be able to have adventures and family, while women need to give one up, at least for a while. Pregnancy, birth and being the one with boobs makes it hard to extricate yourself at first, but all too often this seems to lead into forever. Why?

There have always been daring women scattered about, but female participation in ‘adventure sports’ is quite recent, especially as a (relatively) mainstream thing. The 1980s was the decade when women started blazing some serious trails: those who began adventuring in earnest include US climber Lynn Hill; Kiwi guide Lydia Bradey (the first woman to climb Everest without oxygen); Alison Hargreaves, the British climber who was the first woman (and second person) to climb Everest solo and unassisted; and our own Brigitte Muir, the first Australian to climb the Seven Summits. Other women have followed in every field. Female participation in school and university outdoor education programs is growing, and there are now female-only adventure races, grants and trekking programs, as well as many events, companies and groups aimed at getting women outdoors. But we’re still a long way behind.

There are obvious physical factors as to why mothers stop adventuring. Lexi DuPont, an American pro skier, pointed out in Outdoor Onlinethat a mother would be likely to take at least a year off from intense skiing while having a baby, ’whereas a father’s going to keep hard-charging every day until the baby comes and likely get to keep skiing while a mother attends to recovery, breastfeeding, and all the other biological realities of having a baby’.

Even women who keep adventure fit – climbing, bushwalking, kayaking, swimming, trail running; whatever their bag – tend to reduce the intensity and amount of their activity, for a while at least. During this time they generally pick up more of the household responsibilities just as their confidence, fitness, active involvement and sense of belonging in that space diminishes. Add in multiple kids, where just as you’re getting back into adventure you’re preparing to pause again, and it’s easy to see how a year can turn into a decade with relatively little outdoor action.

There are countless examples of women missing out on adventure due to pregnancy and it’s aftermath. Top US climber Beth Rodden couldn’t even walk around the block for four months following the birth of her son. Alina McMaster, Australian adventure racing legend and the owner of outdoor event business AROC Sport, organised for the AROC team to get back together after a six-year break to celebrate her 40thbirthday. But when they lined up at the start of the Abu Dhabi Adventure Challenge, it was without the birthday girl: McMaster was pregnant.

(I feel awkwardly compelled to add that of course there are sacrifices in having kids, and they are worth it in the long run. But this physical component of the childbearing caper goes for a minimum of one year per kid, is emotionally and physically hard, and is generally overlooked or massively downplayed.)

If it were only about biological differences, there would be a dip of a year or so, then a gradual return to normal. But that’s not the case. What seems to happen, with the women I come across at least, is that adventure and fitness become sidelined for years in a much bigger way than with their partners. Di Westaway, founder and ‘Chief Adventure Chick’ of Wild Women on Top, blames it on societal pressure. ‘It’s not okay for mum to go out just for her own health, or that’s the story we tell ourselves and it’s accepted by the community generally. Your mum role is that first and foremost you have to care for everyone else first.’

There’s also the fact that women statistically earn less and work less, so tend to take on more of the childcare and housework (cleaning, life admin and everything else) than men, as well as carrying the mental load of keeping the family life running smoothly. Getting away is harder if you’re the one who keeps the ship afloat. I know this one firsthand: it took me a couple of weeks of solid organising to prepare for a two-week trek in Nepal last year, and a few days of catch up on my return. This was excluding my own (paid) work and arranging the childcare – it was menu planning, shopping and cooking; arranging schedules, logistics and writing list after list; putting backups in place and a million or so other little jobs. My husband goes away for a similar time and his preparation amounts to planning his trip and packing his bag. Fair? No. But I can I see how it’s happened.

This trade-off between parents grows more pronounced as the seriousness increases, something Dinah Taprell understands well. Her husband Neill Johanson finished the Seven Summits two years ago and he gave up the risky stuff, but she still has very mixed emotions about being married to a mountain climber, feeling both irritation and pride. She recounted a conversation they had about the balance between partners. ‘Neill said,“I don’t think I could have achieved what I did if we had done it in a more equal way, with you (Dinah) getting the time to do what you wanted to do.”‘ But that’s what it comes down to when you’re co-parenting: the more time one person devotes to something, the less time there is left for the other.

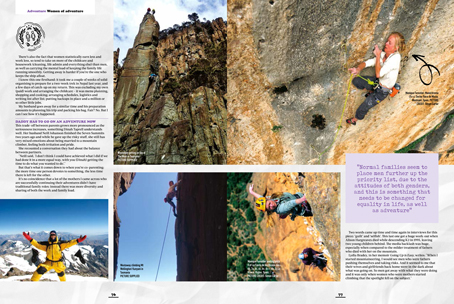

It’s no coincidence that a lot of the mothers I came across who are successfully continuing their adventures didn’t have traditional family roles: instead there was more diversity and sharing of both the work and family load. ‘Normal families’ seem to place men further up the priority list, due to the attitudes of both genders, and this is something that needs to be changed for equality in life, as well as adventure.

Two words came up time and time again in interviews for this piece: ‘guilt’ and ‘selfish’. This last one got a huge work-out when Alison Hargreaves died while descending K2 in 1995, leaving two young children behind. The media backlash was huge, especially when compared to the milder treatment of fathers who died with her on the mountain. Lydia Bradey, in her memoir Going Up is Easy, writes, ‘When I started mountaineering, I would see men who were fathers pushing themselves and taking risks. And it seemed to me that their wives and girlfriends back home were in the dark about what was going on. So men got away with what they were doing and it was only when women who were mothers started climbing that the spotlight fell on the subject.’

Women can (and do) feel guilty for just about everything, but leaving the family behind is a sure-fire way to ramp it up. This guilt often comes from within, or from the imagined disapproval of others, making it even harder to deal with. Monique Forestier, one of Australia’s best climbers, summed up the torment. ‘I have gone through a lot of phases in my life where I feel guilty if I go climbing. I think, “Oh, I should be taking care of my child”. But it’s a really good thing for me to have a break, regardless of what I’m doing with that time: climbing or housework or work.’

Part of this guilt may be from a lack of visible role models. The proportion of high-profile women undertaking risky adventures is small: using mountaineering as an example, it’s estimated that one per cent of first ascents, and around six per cent of Everest ascents, have been done by women. And of these, a much smaller slice are also mothers. Many adventuring women decide that having children is incompatible with their lifestyle. Bradey was sterilised in her early 20s, telling Outdoors Onlinethat, ‘I wanted to travel the world, be a mountaineer, and have adventures… It was a pretty simple decision at the time.’

Even among those who decide to have kids, there is often the feeling that it will be the end of their hard-core days. When asked if she was nervous about how having a child would affect her climbing, Forestier mused, ‘I don’t remember thinking, “I wonder how this is going to pan out with my climbing”. I guess I assumed that it was going to be the end of my hard climbing as I didn’t think it would be an option after having a child.’

Men have had a range of adventuring role models since forever, from Captain Cook to Mawson, Edmund Hilary to Neil Armstrong, and whether they had kids or not didn’t come into the equation. These men aren’t just seen as heroic, they are seen as the pinnacle of manhood. The reception of female equivalents is more uneasy; less wholehearted. These athletes are seen as strong, mentally and physically tough, but these and other ‘manly’ traits and descriptions are more complicated compliments for women.

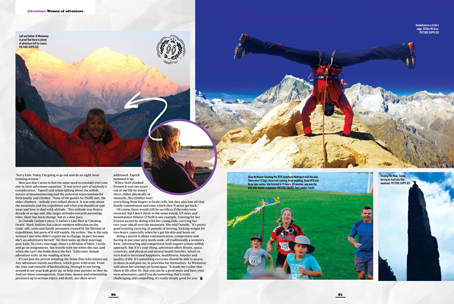

The motivations for adventure change with age, becoming less about competition and more about enjoyment, fitness and the family. The timing of the child-bearing years – smack bang in physical prime-time – force a break from any hard-core competition. This reduces the visibility of women in the space, but doesn’t mean they’ve stopped. McMaster is one example, still competing in adventure races but for different reasons. ‘Having kids didn’t really change my competitiveness but what it has changed, one of the reasons I started doing events again, is to show the kids that it doesn’t matter how you go. You don’t have to win.’ She also talked about how her kids are now at the stage where they can join in. ‘Why I don’t want to make a comeback – aside from the training and the pressure – is I’d actually prefer to do a little adventure with the kids than say, “Sorry kids. Today I’m going to go out and do an eight-hour training session”.’

Men just don’t seem to feel the same need to consider everyone else in their adventure equation. ‘It was never part of anybody’s consideration’, Taprell said when talking about the selfish nature of mountaineering and the potential repercussions for both family and climber. ‘None of the guides he (Neill) met, the older climbers – nobody ever talked about it. It was only about the mountain and the expedition and what you should eat and wear and how to deal with altitude.’ This attitude was from a decade or so ago and, like larger attitudes towards parenting roles, there has been change, but at a slow pace.

InOutdoor Online’s piece ‘A Father’s Last Shot at Cheating Death’, Mark Jenkins has a more modern reflection on the trade-offs, costs and family pressures created by his lifetime of expeditions, but parts of if still rankle. He writes, ‘Sue is the only woman I met who didn’t expect me to change, in part because she’s an adventurer herself.’ He then sums up their marriage post-kids: ‘In every marriage, there’s a division of labor. I write and go on assignments. Sue travels with me when she can, and when she can’t she holds down the fort.’ Kids enter, female adventure exits, in my reading at least.

It’s not just the person minding the home fires who misses out. Any adventure entails sacrifices, which grow with scale. From the time and toenails of bushwalking, through to not being around to see your kids grow up, or help your partner as they do. And yet these consequences, from time, money and relationship pressures up to serious injury and death, are often never addressed. Taprell summed it up: ‘When Neill climbed Everest it was two years out of our life he wasn’t there, either physically or mentally…The climber loses everything from fingers to brain cells, but they also lose all that family commitment and time which they’ll never get back.’

Of course there would still be sacrifices if the roles were reversed, but I don’t think to the same extent. US skier and mountaineer Hilaree O’Neill is one example, training for her Everest ascent by skiing with her young kids, carrying her two-year-old all over the mountain. She told Outside, ‘It’s pretty good training carrying 35 pounds of moving, kicking weight for two hours, especially when he’s got his skis and boots on’.

Being a parent is about communication, compromise and having to put your own needs at the back of the pile: all traditionally a women’s forte. Adventuring and competition both require a more selfish approach. But if it’s your thing, adventure offers so much, including fitness, space, creativity, and physical and mental health benefits, which in turn lead to increased happiness, healthiness, balance and quality of life. It’s something everyone should be able to access, to share in and pass on, to prioritise for themselves. As Westaway said about her attempt on Aconcagua, ‘It made me realise that there is life after 40, that you can be a good mum and have your own adventures, and if you do something that’s really challenging and compelling, it’s really deeply good for you.’