I'm always amazed by the adventures people get up to, especially the sort of fly by the seat of your pants, make it up as you go along kind that seem to happen without a great deal of thought, preparation or expertise. They seem so much more achievable - and fun - than the intensive training, dedication and focus needed for the hardcore challenges. Andrew Bain, Andrew Hughes and Sandy Mackinnon all confirmed my suspicions: to make this type of adventure work, you need to be optimistic, flexible and adventurous, have a sense of humour, and not be too fussy about creature comforts…

The article was a cover story in Australian Geographic Outdoor, Sept/Oct 2009.

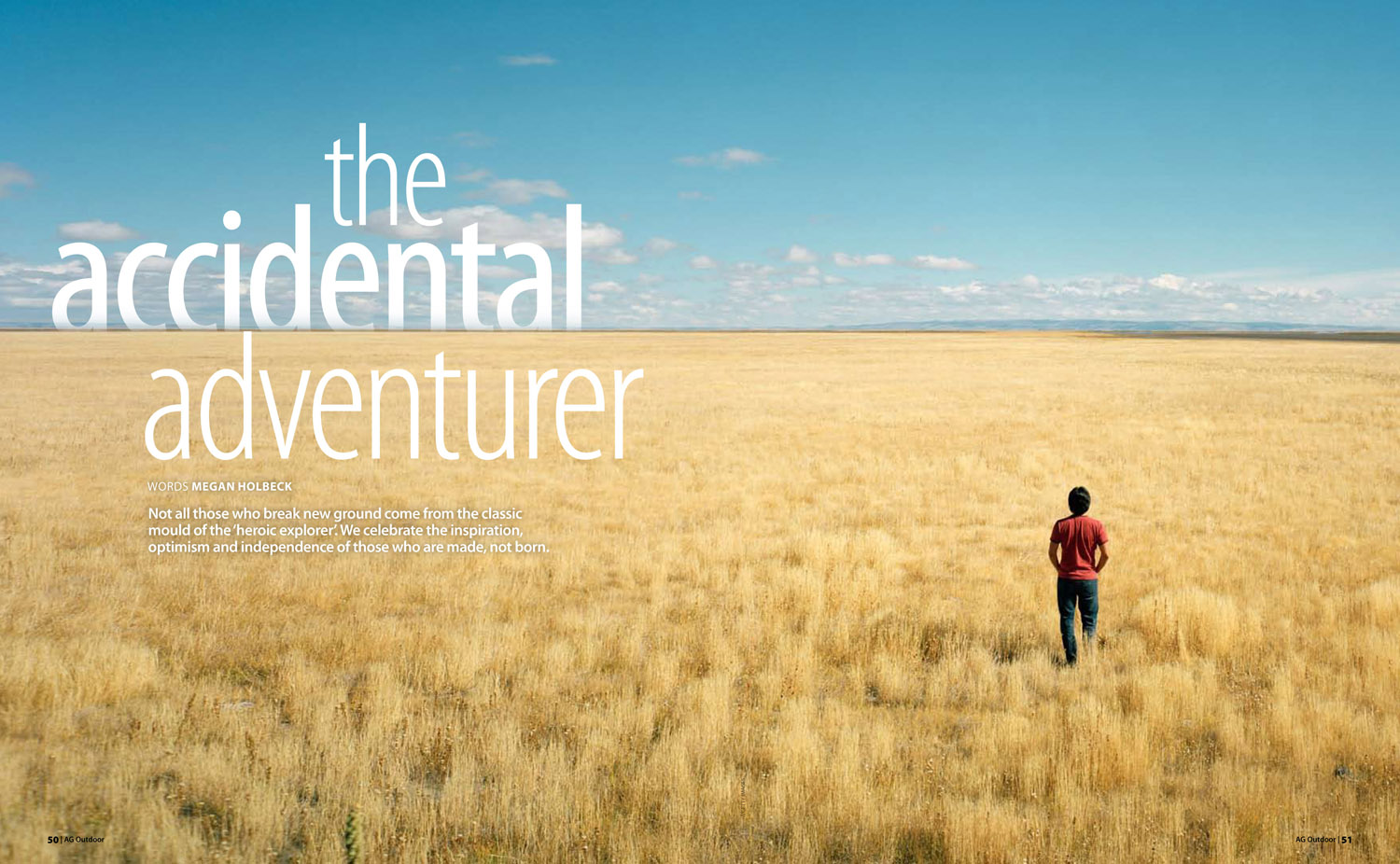

The Accidental Adventurer

Not all those who break new ground come from the classic mould of the ‘heroic explorer’. We celebrate the inspiration, optimism and independence of those who are made, not born.

Words: Megan Holbeck

Ah, the heroic explorer: is there a nobler stereotype? Born for adventure, he escapes his cot for mountain crawls, his knees hardening to chain mail. A childhood spent outdoors equips him with botanical knowledge, navigation skills, the ability to live off the land and possibly communicate with the animals. He runs, he climbs, he paddles, he cycles; he’s phenomenally fit and has biceps the size of small wombats. His logical brain and command in every situation make him a leader, while his drive propels him past every obstacle. He’s the youngest, fittest, strongest member of every expedition - exploration and daring are his calling. By the age of 20 he’s become the first Australian to ice-skate backwards to the North Pole, rescuing drowning polar bear cubs and raising five million dollars for their rehousing on the way, while also discovering a new type of tundra which just might reverse global warming. His next 15 years are mapped out in a schedule of trips and media schedules, a band of teammates standing by to join in. He is, indeed, a man among men. (And yes, it is invariably a man.)

There are many who fit this mould, who have become household names through their daring, courage and achievement. Known by a surname, they are familiar from history, bank notes, books and movies: Mawson, Hillary, Shackleton, Scott. Australia has produced its fair share, filling the pages of our history and this magazine. But this article isn’t about them, and you know why not? Well, first of all, it’s been done - if you want to read about Hillary, you don’t need us to write it, it’s waiting in your local library. And, scandalous though it is to say, aren’t the ‘noble hero’ types just a tiny bit dull? Doesn’t that earnest striving, planning and devotion seem like all work and no play? Not to belittle anyone’s achievements here, but isn’t it more interesting when things are a bit slapdash? Personally, you can't help but love a bit of making it up as you going along; the ‘she’ll be right’ attitude that we Aussies are known for. Not every adventure can start off with a purpose and a noble objective. If Mallory wanted to climb Everest ‘because it was there’, what’s wrong with a motive such as: ‘I had some spare time and wanted to see what would happen.’

Welcome to the world of accidental adventurers (AA), people like us who just happen to do things that are bigger than they are; who bumble their way through, seeing what happens; who let the adventure dictate their direction. And who often have absolutely no idea what they’re getting themselves into. Take an ordinary person, inject a loony streak, arrange a bit of free time, remove all doubt, and ta dah—one accidental adventurer in waiting.

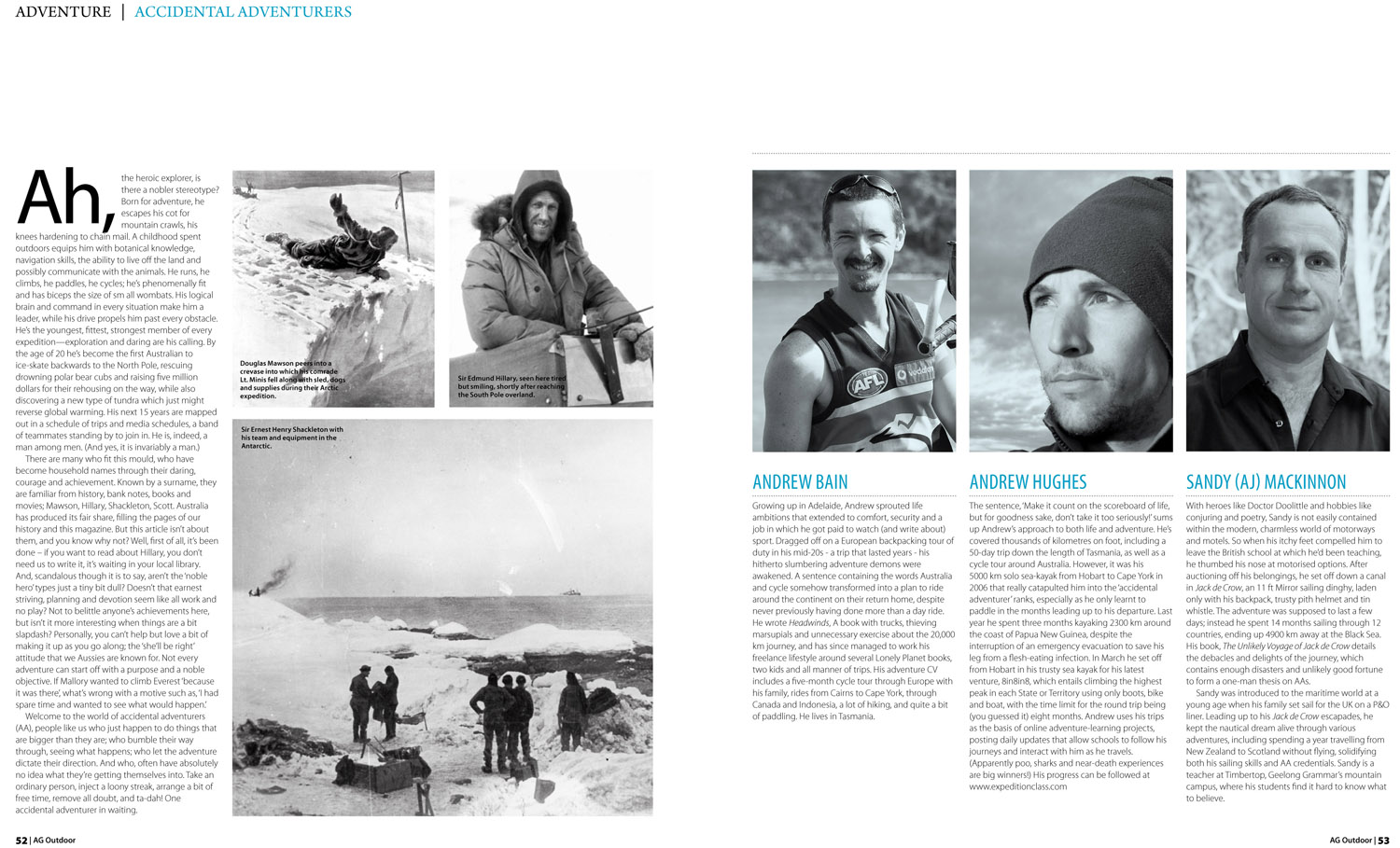

Andrew Bain

Growing up in Adelaide, Andrew sprouted life ambitions that extended to comfort, security and a job in which he got paid to watch (and write about) sport. Dragged off on an European backpacking tour of duty in his mid-20s - a trip that lasted years - his hitherto slumbering adventure demons were awakened. A sentence containing the words ‘Australia’ and ‘cycle’ somehow transformed into a plan to ride around the continent on the return home, despite never previously having done more than a day ride. He wrote Headwinds, ‘A book with trucks, thieving marsupials and unnecessary exercise’ about the 20000 kilometre journey, and has since managed to work his freelance lifestyle around several Lonely Planet books, two kids and all manner of trips. His adventure CV includes a five-month cycle tour through Europe with his family, rides from Cairns to Cape York, through Canada and Indonesia, a lot of hiking, and quite a bit of paddling. He lives in Tasmania.

Andrew Hughes

The sentence, ‘Make it count on the scoreboard of life, but for goodness sake, don’t take it too seriously!’ sums up Andrew’s approach to both life and adventure. He’s covered thousands of kilometres on foot, including a 50-day trip down the length of Tasmania, as well as a cycle tour around Australia. However, it was his 5000 kilometre solo sea-kayak from Hobart to Cape York in 2006 that really catapulted him into the ‘accidental adventurer’ ranks, especially as he only learnt to paddle in the months leading up to his departure. Last year he spent three months kayaking 2300 kilometres around the coast of Papua New Guinea, despite the interruption of an emergency evacuation to save his leg from a flesh-eating infection. In March he set off from Hobart in his trusty sea kayak for his latest venture, 8in8in8, which entails climbing the highest peak in each State or Territory using only boots, bike and boat, with the time limit for the round trip being (you guessed it) eight months. Andrew uses his trips as the basis of online adventure-learning projects, posting daily updates that allow schools to follow his journeys and interact with him as he travels. (Apparently poo, sharks and near-death experiences are big winners!) His progress can be followed at www.expeditionclass.com

Sandy (AJ) Mackinnon

With heroes like Doctor Doolittle and hobbies like conjuring and poetry, Sandy is not easily contained within the modern, charmless world of motorways and motels. So when his itchy feet compelled him to leave the British school at which he’d been teaching, he thumbed his nose at motorised options. After auctioning off his belongings, he set off down a canal in Jack de Crow, an 11-foot Mirror sailing dinghy, laden only with his backpack, trusty pith helmet and tin whistle. The adventure was supposed to last a few days; instead he spent 14 months sailing through 12 countries, ending up 4900 kilometres away at the Black Sea. His book, the Unlikely Voyage of Jack de Crow, details the debacles and delights of the journey, which contains enough disasters and unlikely good fortune to form a one-man thesis on AAs.

Sandy was introduced to the maritime world at a young age when his family set sail for the UK on a P&O liner. Leading up to his Jack de Crow escapades, he kept the nautical dream alive through various adventures, including spending a year travelling from New Zealand to Scotland without flying, solidifying both his sailing skills and AA credentials. Sandy is a teacher at Timbertop, Geelong Grammar’s mountain campus, where his students find it hard to know what to believe.

Purpose

‘Nobody climbs mountains for scientific reasons. Science is used to raise money for the expeditions, but you really climb for the hell of it.’ Sir Edmund Hillary

Back in the day, it seems like the whole ‘why’ question was a lot easier. Exploring was done for national pride as well as fame and fortune, with correspondingly dizzying stakes and rewards - you might sail off the edge of the world, but you could also discover riches beyond your wildest dreams. Ready-made reasons for adventuring were lined up like permission slips. These days a purpose may be noble, but the adventure itself is still the real reason that people sign up; to challenge themselves, their ambitions, and their ability to enjoy the experience. In the absence of old-school, ‘my country is tougher than yours’ funded expeditions, modern-day adventuring has almost become a job. Self-promotion and media relations have become important skills in the survival kit for 21st century adventurers, allowing future trips and a livelihood.

In contrast, the motto of accidental adventurers could well be ‘have time, will travel’. In 1932, Oskar Speck left Germany in a folding kayak, heading for Greece where he planned to find work (see AG Outdoor's Jan/Feb 2009 magazine). More than seven years later he landed on Australian soil and was interned as an enemy alien, forgiving us enough to settle here for life. Few people have heard of him yet his was a huge achievement. The journeys don’t have to be as big, but the reasons behind them are the same: to see where the adventure takes you.

This is something to celebrate about our amateur friends: they don’t need to convince anyone else of the legitimacy of their trips. Their self-funded journeys float on enthusiasm and are propelled by personalities: all they have to do is go. As detailed in Mackinnon’s book, the dinghy trip started out as a daydream: ‘My feet were itchy and I felt it was time for a grand gesture and a dramatic farewell…Finally I hit upon it. I decided to leave Ellesmere…by sailing away in a jolly little galleon like my dear Doctor Doolittle, and seeing what I bumped into on the way.’ As he says, ‘I honestly thought I’d only get two or three days down the river and it’d peter out. It was lovely to find that I could keep going around the next bend’. And it was this mentality took him all the way to Bulgaria!

The reasons for setting off are as diverse as the personalities involved, generally beginning with variations on boredom, moving through the stages of rash commitment and basic logistics to end up with the excitement of tackling an individual, wacky mission. The Bains had spent years toodling around Europe, returning home with the knowledge that they were part of: ‘A generation (that) had seen more of the opposite side of the world than it had its own backyard. It was like trying to know somebody else before you know yourself.’ Three months after the first suggestion of a cycling trip, they set off from Cairns, aiming to absorb Australia kilometre by kilometre, correcting the idea that adventures were things that only happened elsewhere, generally overseas. Fourteen months of riding into the prevailing winds gave them the opportunity for a very slow appraisal and new appreciation of their own continent.

A big part of the allure of these adventurers is that they don’t let obstacles - the lack of planning and preparation, the doubters and deniers, the worries of themselves and others - get in the way. There are always good reasons not to do something, while for most people ‘because I want to’ seems a light counterbalance. But as Andrew Hughes explains it: ‘I struggle to imagine anything else I could do that could give me so much. I wake up and think, “God, I want to go and do that today”. And as soon as I am on another trip I want to plan the next one because it gives me something to wake up and be excited about.’

Inner resources

‘There are two kinds of adventurers: those who go truly hoping to find adventure and those who go secretly hoping they won’t.’ Rabindranath Tagore

Adventurers are typically fairly heavy on inner resources; determination, drive and leadership. These are the things that keep them going through all the pony-eating, frostbitten moments - they have the strength of character to know that theirs is a goal worth pursuing and the force of mind to convince others. And for our more everyday heroes? It is some of the above, accompanied by a hopelessly optimistic outlook, a fascination with people and the magic of the everyday, and a reliance on small rewards—chocolate, showers, rest days.

Contrary to the explorer stereotype, the adventurous impulse is not innate. Although two of my three AA examples had childhoods in the rugged outdoors, Andrew Bain certainly did not. His early adult life revolved around football, the pub and his job—as he puts it in Headwinds, ‘they had hardly been the formative years of adventurous spirits’. HIs wife Janette’s desire to travel wore away at Andrew until he agreed to backpack around Europe. ‘I was as cheap as I was sedentary…insisting that we camp our way around the Continent. It became, like cycling around Australia would, a matter of pig-headed resistance. As we toured around, a lust for adventure budded in me like spring. My travel ambitions drew level with Janette’s, then became her monsters.’ Little did they know it then, but an AA was being born. The plan to cycle around Australia was hatched shortly afterwards, followed by a steady stream of other adventures.

A fascination with their environment and the people in it is a common trait for adventurous types; interesting asides and characters can be found everywhere from city buses to the Bulgarian countryside. As Andrew Hughes puts it: ‘If you’re open to people, then people become open to you.’ It’s not that AAs find everyone and everything fascinating; it’s that it all genuinely is. This is why they go on trips in the first place: to experience their lives as the adventure they are, rather than becoming disinterested spectators of their own daily grind. Hughes again: ‘Adventures put life in perspective: they make me realise that what I’m doing and what my life is aren’t that important. If it all goes wrong and it all collapses around my ears, then so what? It’s just one person in a big, bad world.’

An optimistic outlook is a necessity; without it you can’t overcome other people’s doubts, let alone your own, and you’d be easily seduced by the safety of home. Further down the track, the 15th day of headwinds, porridge, or flat, uninspiring riverbanks would be your last unless you truly believed that something inspiring and monumental would happen, and were able to recognise that magic in the kindness of a stranger, a good sleep or a pint at the pub. However, this optimism has a dual purpose - it allows the journey but masks the danger, hence the constant scrapes faced by AAs. Sandy’s attitude captures this well: ‘I always very sincerely feel that people are going to want to be helpful, that if you approach anybody they are going to go: “How can we help you, what do you need? Please let us adopt you as our long-lost son.” While it’s great to be optimistic about people, I’m also recklessly optimistic about things like weather. It doesn’t matter how cheerful you are or how many jaunty little tunes you play on your tin whistle, it doesn’t make the storm go away or the rock face get any less dangerous.’

Andrew Hughes’s online diary of his Papua New Guinea paddle also contains supporting evidence. Eight days after the first symptoms of a ‘bung knee’ develop, he diagnoses a boil and claims that by the next day, he’ll be ‘100 per cent’. The next entry details his evacuation to hospital, slipping in and out of consciousness, and the operation to drain the wound and prevent infection spreading to the bone. Within three days he joyfully announces, ‘Today I left the dark chamber of thunderbolts and long shadows and entered the glittering dome of sago-palm filtered sunlight’, while throughout his 16-day recovery he confidently predicts that he’ll be right in a week!

Everyday heroes have something else which appeals, especially to Australians: humility and humour. There are none of the rash, brash, pre-emptive boasts of ‘best’, ‘first’ and ‘limits of human endeavour’, no massive egos that need constant stoking. In fact, the ‘brag offs’ that are an all too common in outdoors circles are completely absent. AAs keep their profiles small and themselves approachable - there are no ‘tall poppy’ worries if you’re your own biggest denigrator. When asked, the Bains claimed that they were only cycling down the east coast of Australia, reluctant to reveal their real plan until they were sure they could live up to the expectation, while Mackinnon stuck to his ‘rowing to Bristol’ story until his plan to cross the English Channel was all but concrete. The independent, self-sufficient nature of an AA marries nicely with their purpose: they’re not doing it to prove something to other people, they’re doing it for themselves.

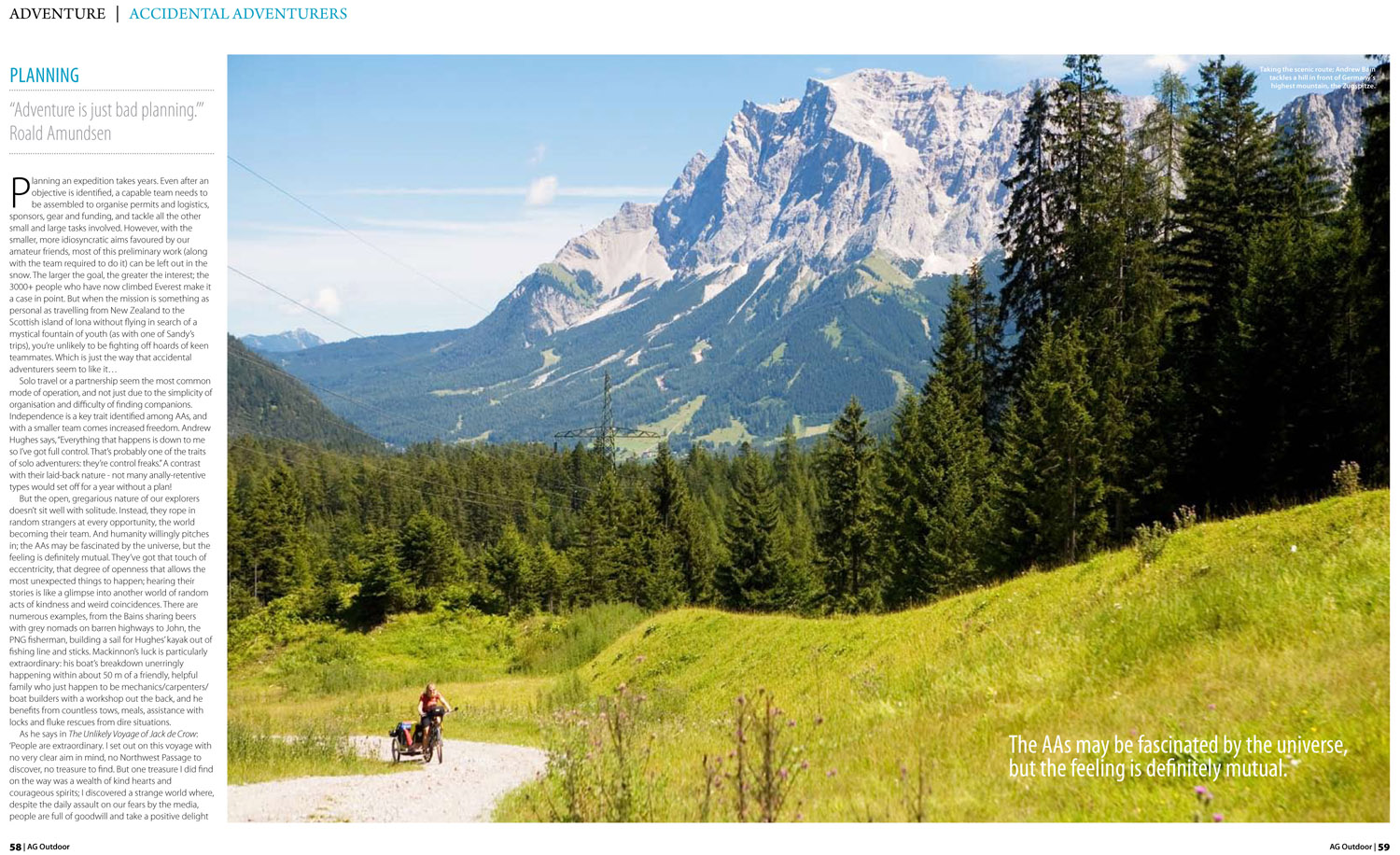

Planning

‘Adventure is just bad planning.’ Roald Amundsen

Planning an expedition takes years: even after an objective is identified, a capable team needs to be assembled to organise permits and logistics, sponsors, gear and funding, and tackle all the other small and large tasks involved. However, with the smaller, more idiosyncratic aims favoured by our amateur friends, most of this preliminary work (along with the team required to do it) can be left out in the snow. The larger the goal, the greater the interest: the 3000+ people who have now climbed Everest make it a case in point. But when the mission is something as personal as travelling from New Zealand to the Scottish island of Iona without flying in search of a mystical fountain of youth (as with one of Sandy’s trips), you’re unlikely to be fighting off hoards of keen teammates. Which is just the way that accidental adventurers seem to like it…

Solo travel or a partnership seem the most common mode of operation, and not just because of the simplicity of organisation and difficulty of finding companions. Independence is a key trait identified among AAs, and with a smaller team comes increased freedom. As Andrew Hughes says, ‘Everything that happens is down to me so I’ve got full control. That’s probably one of the traits of solo adventurers: they’re control freaks.’ A contrast with their laid-back nature - not many anally-retentive types would set off for a year without a plan!)

But the open, gregarious nature of our explorers doesn’t sit well with solitude. Instead, they rope in random strangers at every opportunity, the world becoming their team. And humanity willingly pitches in: the AAs may be fascinated by the universe, but the feeling is definitely mutual. They’ve got that touch of eccentricity, that degree of openness that allows the most unexpected things to happen: hearing their stories is like a glimpse into another world of random acts of kindness and weird coincidences. There are numerous examples, from the Bains sharing beers with grey nomads on barren highways to John, the PNG fisherman, building a sail for Hughes’s kayak out of fishing line and sticks. Mackinnon’s luck is particularly extraordinary: his boat’s breakdowns unerringly happening within about 50 metres of a friendly, helpful family who just happen to be mechanics/carpenters/boat builders with a workshop out the back, and he benefits from countless tows, meals, assistance with locks and fluky rescues from dire situations.

As he says in The Unlikely Voyage of Jack de Crow: ‘People are extraordinary. I set out on this voyage with no very clear aim in mind, no Northwest Passage to discover, no treasure to find. But one treasure I did find on the way was a wealth of kind hearts and courageous spirits; I discovered a strange world where, despite the daily assault on our fears by the media, people are full of goodwill and take a positive delight in trusting each other. It seems the best way to get there is by Mirror dinghy.’

‘Most adventures begin with the infinite detail of planning and preparation. Months of obsessive thought, studying maps, fine-tuning equipment, carefully selecting inventory, training like Olympians, and the readying for any eventuality. Not this adventure.’ This passage comes from Bain’s book, but applies equally well to the journeys of our other two AAs. Mackinnon overlooked his lack of rowing ability before setting off in his dinghy, and within the first two days he’d lost his toolkit, his boat (temporarily), his map, one rowlock and gunwale, been electrocuted numerous times and busted naked (apart from his pith helmet) by three female canoeists. For his part, despite paddling up the east coast of Australia and covering a good chunk of PNG shoreline, Hughes still hasn’t mastered the Eskimo roll. Of course, our AAs have skills that compensate for those they lack: solid sailing, walking, outdoors and survival experience, as well as first-aid, commonsense and general knowledge. This seemingly simple planning approach is summed up by Andrew Bain: ‘As long as you’re not putting yourself in danger you can learn as you go along. I wouldn’t go to the Antarctic without preparing massively, but if you’re doing a cycle trip or something, just buy a map and go.’

Planning is done within known constraints, which lend their flavour to the whole trip. As Mackinnon admits, part of the point of travelling by dinghy was that it was more difficult and he could force himself to have a good, old-fashioned adventure. Andrew Hughes’s latest trip, 8in8in8, was heavily influenced by cost: he left from and will return to Hobart by sea kayak to save the cost of airfares and shipping. And when it comes to necessary gear and equipment, the one thing emphasised over and over again was how little was needed to get by. As Mackinnon put it: ‘Travel very, very light. But take a pith helmet, because then people rightly or wrongly fall in love with you and know that you’re mad but not dangerous.’

A big part of the appeal of this type of adventure is that although they’re wonderful, inspirational trips, they’re not unattainable for mere mortals. They are the sort of personal, doable challenges that are within the reach of anyone with enough imagination to visualise an adventure, courage to overcome doubts and barriers, and optimism to see positives rather than impossibilities. There are literally thousands of examples of people choosing their own adventures and making them happen - a quick trawl of the web will reveal Aussies rowing across oceans, unicycling across states, paddling up coastlines and marching across deserts. The challenges don’t even have to be that big: after all, one person’s Kosciuszko may be another’s Everest. And if, in achieving your goal, you can brighten the lives of others on the way, regale them with stories and anecdotes and inspire others to take on their own challenges, so much the better. As Sandy Mackinnon says, ‘Most people don’t seem to realise that once you untie yourself from everything, you can do anything. I met so many people along the way who said, “Oh you’re so brave. I wish I could do what you are doing.” And I’d say, “Well, you can”.’